Article by Gilbert A. Bouchard

-The Journal 2002

Article by Gilbert A. Bouchard

-The Journal 2002

Article by Elizabeth Beauchamp

-The Journal 1992

Shut Out- High costs of rent forces artists to leave the core

By Mari Sasano

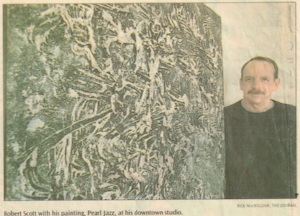

Art Review: Robert Scott

Published in Canadian Art 1988

Profile of an Artist: Robert Scott

by Gordon Novak

Published in Opulence Magazine

In the tranquil misty light of Tao Hua Tan, Canadian abstract artist Robert Scott began his month-long residency program at The Peach Blossom Pool Holiday Hotel. From the very moment Scott and his wife Susan arrived at Shanghai International Airport, the pair were treated like royalty. A red carpet guided the two up the grounds of The Peach Blossom Pool Holiday Hotel, towards their five-star room and down into a banquet hall celebrating the arrival of 40 international artists attending the first annual residency program.

Sculptures at The Peach Blossom Pool Holiday Hotel

Red carpet entrance at the opening ceremony.

Inside Robert Scott's five star hotel room.

Monument outside hotel grounds

Inside the hotel's greenhouse, where Robert Scott set up his studio.

Inspiration came naturally to Robert Scott as the residency program offered a variety of activities such as artist talks, studio arts and printmaking workshops, as well as a tour of a local handcrafted paper and printmaking company: The Chinese Xuan Paper.

"Inspiration was found everywhere we went. From the traditional sculptures on the grounds of the hotel, to watching the practice of making handcrafted paper; some of which takes five years to make. It was truly an incredible experience."

Robert Scott working in The Peach Blossom Hotel's greenhouse.

Robert Scott with program organizer and esteemed printmaker Gordan Novak.

Robert Scott with fellow artists attending the residency program.

Children from a local school in Tao Hua Tan lining up to view Xuancheng Exhibition

Scott and the other international artists attending The Peach Blossom artist residency had the opportunity to select the location of their studio space from the grounds of the hotel. Built on top of a historic town in Tao Hua Tan, Robert Scott decided to work in The Peach Blossom Hotel's greenhouse. "I was very impressed with this artist residency's ability to bring together so many different artists and allow them to feed and thrive off one another's energy, it resulted in very interested art being created."

The culture and beauty of his surroundings gave way to three works of art that were well received during the public Xuancheng Exhibition at the end of his month long residency and is currently part of The Peach Blossom's private art collection.

Check out this wonderful article about my Copper Slag series by Jeffrey Spalding.

My latest work "Black Waters" will be featured in the 1st Annual Autumn Show at Udell Xhibitions. Established in 2017 by Andrew Udell and Melissa Lavoie, Udell Xhibitions is a hidden Edmonton gem, exhibiting unique works of art. Each year, the gallery hosts a number of exhibitions, programs, and events that help bring the public closer to the world of art.

Exhibition runs from Sep 14 - Sep 30 For more information visit Udell Xhibitions

I am honorued to be one of the few artists selected from Canada to be invited to participate in the 1st International Artist Retreat and Residency Program located in Tao Hua Tan, Anhui Province, China from October 10th, 2017 – October 25th, 2017. During the duration of the residency program, I am required to create three works of art (one painting on canvas size 120 cm x 120 cm and two more works on canvas size 60 cm x 60 cm) that will become part of the permanent collection of the organizer’s future World Art Museum at The Peach Blossom Pool Arts and Holiday Riverside Resort, Tao Hua Tan, Anhui Province, China. I will spend an additional 7 days in China participating in cultural and artistic research and exploration, touring specific architectural sites, local artist studios, and museums based on my findings during the residency program.

Robert Scott and the Big Picture

TIM NOWLIN

"Bronze Drama" 1992. Acrylic on canvas, 96 x 72.5 in.

The opportunity to comment on the work of Robert Scott has, in certain ways, forced me to focus more clearly on considerations and reconsiderations of modern abstract painting. Serious questions regarding the viability of modern abstraction have already been raised and questions of my own occur upon every viewing of new abstract paintings. In the age of Postmodernism, with its deep scepticism of modernist and other certainties, how does one approach and evaluate contemporary abstract paintings? Have the myths and realities of modern painting been undone by a re-evaluated knowledge of our illusions?

These kinds of questions have also been prompted recently by my looking again at the great abstract paintings from the 1940s through the 1960s; Canadian and American as well as European. I am still astonished, as I had been earlier in life, at the sheer power and presence of the paintings of Jackson Pollock, for example, or Willem de Kooning or Jean-Paul Riopelle. In Europe, I was equally impressed by the major works of Pierre Soulages, Antoni Tapies, Bernard Shultze and Han Tier. Again, I ask myself how these paintings can remain so powerful, weathering time with their incredible presence and probity intact.

How then do I approach and introduce the paintings of Robert Scott? I've always liked Scott's work precisely for its physical presence and now must ask myself why I prefer his work to a great deal of other recent abstract painting. I like his later work even more and feel that in the best paintings, Scott is proving himself as an artist of considerable strength. His paintings, like those of all serious modern painters, refer ineluctably to their own making, yet reveal, as well, an intense and intimate process of sublimation. It is in that respect that Robert Scott is essentially a romantic painter and, I believe, from this realm that his paintings gain their strength.

Scott's paintings are neither timid nor half-hearted. They impose themselves physically as much as visually. They exert their objecthoodthrough thick and lush encrustations of paint which, in their most extreme, leave two-dimensionality behind. In creating big pictures (and even his works on paper are big), Scott literally and physically creates a highly animated wall of paint.

It is obvious that Robert Scott celebrates and emulates both painterliness and expression and has an affinity to painterliness in all of its past manifestations. It is equally obvious, however, that there is an important and specific connection to the final liberation of surface and the all-over painting first achieved by Pollock. It is to this brief moment in the history of painting, with its immense aftershocks, that Scott's work seems essentially tied.

It seems so mundane now as to be easily dismissed, but we forget how extremely radical was the final barrier of the surface. It was like the sound barrier. Many believed (and apparently still believe) that for painting to become entirely surface, as discrete object the being of painting, without reference to another subject or space, was impossible, even though its implication had lain at the very roots of modern painting. Paul-Emil Borduas, one of Canada's most radical painters, was nervously reluctant to take this final step. Modern painting, through Pollock, had gained complete objecthood. Illusionary space, the metaphorical glue of painting since the Renaissance, had finally been eliminated.

It is equally relevant that Scott's work is not connected to, nor does it rely on, the theoretical foundations formulated after 1960 by Clement Greenberg and known as Post-Painterly. In fact, his practice is described perfectly by Greenberg in his 1962 definition of painterliness as "loose, rapid handling, or the look of it; masses that blotted and fused instead of shapes that stayed distinct; large and conspicuous rhythms; broken colour; uneven saturations or densities of paint; exhibited brush, knife, or finer marks, ..."1. Greenberg's observation of the qualities and value sought after in Post-painterly abstraction clearly indicates a concentration on pure colour and openness, neither of which are principles of Scott's method.

In fact, opposing a clear order of pure colour and openness (or a rational ordering of formal areas in relationship to themselves, to the edge of the canvas, etc), there is in Scott's paintings a tendency toward amalgamation, darkness, and cloistering. What appears as expansive is, at the same time, an inward movement. The heavy strata of pigment and gel are involved in a secretive and revelatory process of layering and uncovering and the recorded gestures of the artist can range from small nuances to large pictographic passages.

The paintings are surfaces and, like a sea of tensions and articulation, are the testimony of Scott's practice. The paintings are never reductive nor conceptual.

Although he is an instinctive colourist, Scott's later paintings have abandoned the decorativeness of his earlier paintings in favour of a much more serious self-awareness. Dark copper slag mixed into the paint now replaces sprayed-on veils of colour. There are strong indications, as in titles and paintings such as Taurus, 1993, of an affinity to the very visceral Spanish painters of past and present. In newer paintings such as Lascaux, 1993, he has also poetically reiterated the idea of a wall or surface through an almost divinatory relationship with a graphic, pre-lingual will. Scott reveals, in the recent works, a stronger affinity to European painters generally and possesses a certainty regarding his mission as an abstract painter that one also finds now more in Europe than in North America. Although the paintings remain aware of their roots in expressionist abstraction, and occasionally pay homage to its masters, his work finds many kindred spirits in abstract artists now exhibiting in Europe and Great Britain.2

This seems like a large leap, but Robert Scott's paintings have never really been burdened by the grand telelogical debate that evolved around abstraction in North America and likely benefitted from not adhering to more polemical notions of paintings. Many have thought that the endless variations of an otherwise strict set of parameters that were born from this evolution eventually threatened to reduce modern abstraction to painting that was mannered and repetitive. Many believe as well that the precedents of modern painting will remain irreversible and that to smugly dismiss them is to run the risk of stepping into other ideological quicksands. Introspection is healthy for art, as is the awareness of illusions. Robert Scott is a modern painter in the most basic sense, yet his work ultimately avoids the illusions of fashion and timeliness.

-----

Footnotes

1 Clement Greenberg, "After Abstract Expressionism", Art International 6, 1962, Pp. 24-32.

2 I hesitate to imply a close connection between artists whose work varies so considerably but I refer here to the bold spirit of abstraction.

"Cinitusa" installed at Whitemud Crossing Six Cinemas December 1987

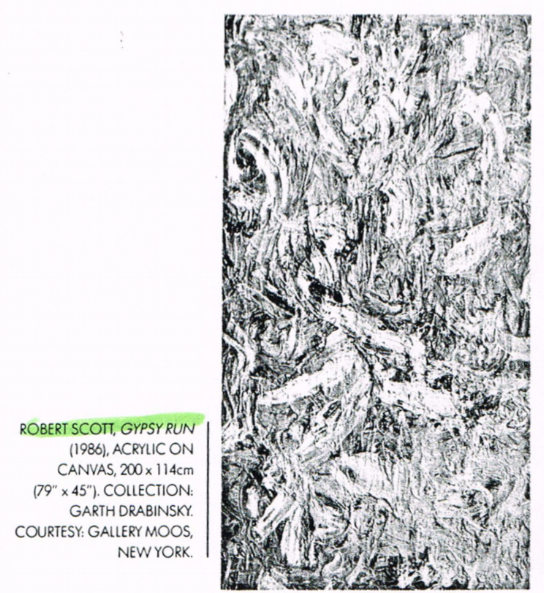

Since the 1940's, when Jackson Pollock made his pictures by dripping and splattering paint on canvas, one aspect of modern painting has been concerned with the relationship between the process of painting and the development of the image. In particular, there has been a great deal of exploration in the methods of relating the image of the painting to the dynamics of its production. This approach balances on the edge between retaining complete control over working procedures and accepting chance or accident, neither forcing the former nor seeking to conceal the latter.

Some ten years ago, Robert Scott began to make his paintings by spraying layers of colour on his canvases and the raking his fingers through the paint. The overall formula appearance of the paintings developed through the pattern of grooves within the paint. This method also created the surface colour of the work as his raking disturbed and mixed the colour layers. In his most recent paintings, however, he has moved away from 'raking,' and has developed two contrasting approaches to the surfaces. One method builds the surfaces in high relief, the paint swept up like wave crests on the point of turning. He generally uses the dominant colour, its effective range increased by the light breaking on the uneven paint surface. The second approach, found in the commissioned works "Cinitsua" and "Cinesubobus", involves spraying and splattering paint. Relatively thin layers of colours play against one another in contrasting hues and graphic structures.

"Ancestral Blues" 1997. Acrylic and Copper Slag on canvas, 37 x 117 in.

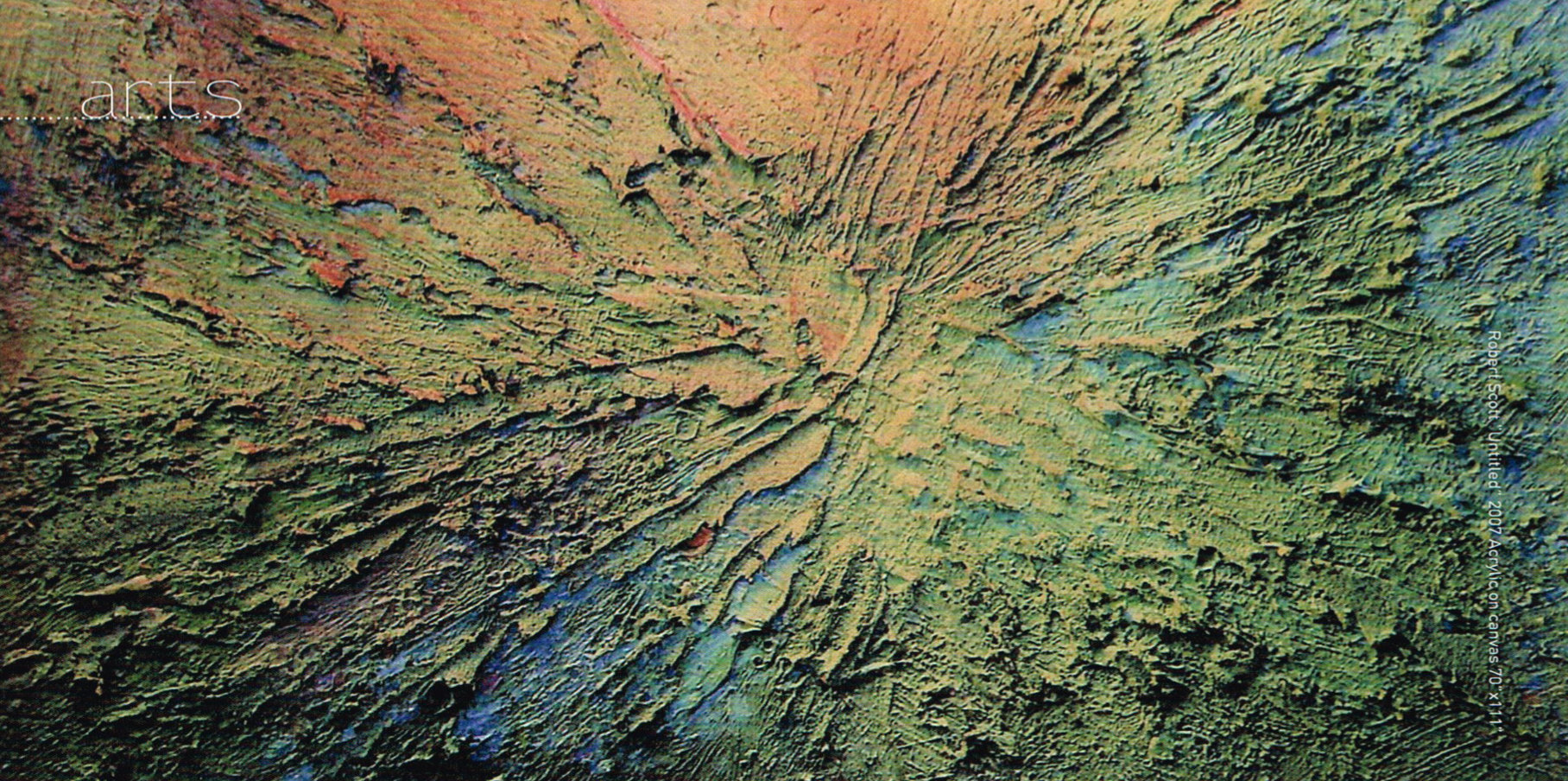

Robert Scott's Recent Paintings

Article by Gilbert A Bouchard

The Edmonton Journal April 28, 2006

Edmonton-based [artist] Robert Scott has been painting tear of late. He's happily ensconced in the new studio not far from his home and is back to painting his familiar heavily textured paintings on old-fashioned stretched canvas. Scott is not only painting prolifically these days, he's also creating work with a substantially different visual focus.

"In these more recent canvases, I'm showing more concern about the centre of images," says the 64-year-old abstract painter known for his gestural work.

He has a showing of 27 works at the Vanderleelie Gallery.

"It's not that I'm drawing from the centre, which is itself a brilliant compositional device, but it's more like I'm producing work that talks about the idea of things radiating out like a starburst creation."

Scott says he finds himself engaging all his senses in the production of this most recent work.

"I'm following the sound of the paint as it's being moved about the canvas as well as being moved by the feel of the paint and its visual effects. It's great to be able to discover all these feelings about how you make paintings and the play that goes into painting them."

Scott has been happy with the effects he's been getting with this new work, in particular the different visual feel the canvases boast, depending on where you stand looking at them and how the light is hitting them.

"For me it's all about creating work that is very comfortable and gives you something to look at on all four sides. I like the fact that the works change a lot depending on what time of day you're looking at them."

Scott will also airbrush different colours of paint on the different sides of his heavy paint ridges, creating some dramatic colour effects. One painting on display seems to shift from gold to blue as you walk from one side of the work to the other, a visual trick Scott equates to the shifting colours and tones that are visible in the sky surrounding the Prairie Sun.

"This kind of exploration goes back to when I was in university and was studying entomology. I was particularly fascinated with how bees followed shifts in UV light to find food. I've long tried to do something similar with my paintings so that they can be enjoyed...across 180 degrees."

Such subtle colour effects are par for the course for Scott, given his long dedication to creating tightly controlled images. For example, the painter is fond of playing warm and cold colours against each other, as well as playing with underpainting and "blacklighting" effects, like subtly "kicking up" streaks of black with shadows of blue in one stark, black pigment-dominated painting.

"I'm the kind of painter who works with light as well as colour," says Scott. "It's all about opening up work and letting it have a life of its own and letting it breath."